Hello there, I made a little video YouTube.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Lines from L’Allegro

Here are my favorite lines from John Milton’s “L’Allegro,” published in 1645.

“L’Allegro” translates from Italian as “The Happy Man.” Milton wrote this and another poem, “Il Penseroso” (The pensive or thoughtful man) as a companion piece. Two moods are contrasted to pleasant effect by this pair of poems.

As with anything written so long ago, footnotes prove essential. One of the better online poetry resources I’ve encountered is The John Milton Reading Room, a project of Dartmouth College. For the full text with footnotes, click here.

Illustration is by William Blake, “Mirth and Her Companions.”

Why Persians Write such Great Poetry

Omar Khayyam and Hafiz – two poets who seem like old friends to me.

When I first encountered Persian poetry, I marvelled at how wonderful it was. One reason? It has an audience… a culture that celebrates, values — and funds –its expression:

— from “A Year with Hafiz” by Daniel Ladinsky. Excerpt from Henry S. Mindlin’s introduction. I highly recommend this book!

Advice from a Persian Poet

Learn to recognize the counterfeit coins

that may buy you just a moment of pleasure

but then drag you for days like a broken

man behind a farting camel.

— from A Year with Hafiz, Daily Contemplations.

Translated / rendered by Daniel Ladinsky

Original poem

Some time ago, while taking a walk in a natural setting, I was seized by an irrational impulse — Poe would call it the “Imp of the Perverse” — to rid myself of my iPhone by hurling into a creek, or dropping it into a clear pool, and watching to see how long it would take for those glittering gem-like app icons to wink out of existence.

Like most healthy people, I have a love-hate relationship with technology, and I wish humanity would make greater attempts to question its utility. The romantic movement was a reaction against industrialization; I hope a new and similar movement will someday take hold in our digital age. There needs to be a backlash on technology’s dominance over our lives and a rediscovery of what it means to be human.

Anyway, this was a poetic attempt on this theme. I don’t know what I’m doing, but I do enjoy the idea of using traditional poetry to address modern subjects. Thanks for visiting!

Rumble Over the Rubaiyat

(This post is part of my ongoing amateur exploration of the Rubaiyat. You might want to check out some of my other posts first)

In the nostalgia section of a local bookstore in Austin, Texas, I came across this …

It should be entitled: “Why everything about Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat is wrong.” It was published in 1967, so perhaps some of the issues it raises are closer to being resolved. Or perhaps scholars have ceased to care: the Rubaiyat fad is over. Graves teams up with Omar Ali-Shah, a Persian scholar, whose family owns the manuscript that serves as an earlier and therefore allegedly more accurate source.

I read two of Graves’s most popular works of historical fiction: I, Claudius and Claudius the God (both of which I would recommend if you’re curious about Roman history). Graves (1895-1985) was a poet, scholar, writer and translator, WWI soldier and author of many works.

Yet all his formidable achievements make his assault on a poetic phenomenon and its author seem petty. Palpably angry, Graves and Ali-Shah share a clear agenda: to reclaim a work that has been done a disservice at the hands of an inept translator, who has not only mangled the words, but warped the very meaning of Omar Khayyam’s spiritual poetry, which is steeped in Sufi mysticism:

“For four generations, indeed, by an evil paradox, Omar Khayaam’s mystical poem has been erroneously accepted throughout the West as a drunkard’s rambling profession of a hedonistic creed: ‘let us eat and drink for tomorrow we die.’ Khayaam is also credited with a flat denial either that life has any ultimate sense or purpose, or that the Creator can be, in justice, allowed any of the mercy, wisdom or perfection illogically attributed to Him; which is precisely the opposite view to that expressed in Khayaam’s original.”

What about all the references to wine and drinking? Well, they can be explained by way of subtle Sufi metaphor: it’s only a figurative drunkenness that Khayyam speaks of — what he is really referring to is the intoxication of divine love. I’m not sure I buy it. The co-authors make some valid points — especially about the liberties Fitzgerald took — but nevertheless, their petulant tone and personal attacks undermine their argument. If you read between the lines, it’s also not clear that their premise is even accepted by a majority of scholars in the field.

I fear that interpreting Khayyam is as fruitless as interpreting Jesus. I could plunge into a study of early Christianity, learn ancient Greek, and still not arrive at definitive answers. Turning to existing authorities, I would encounter a range of biases — can scholars of religion truly be dispassionately objective? It seems everyone wants to claim Khayyam, be it Epicurean Englishman, mystic Sufi, or angry atheist. And Khayyam’s skepticism of religious authorities is apt to raise the hackles of pious Muslims and uptight Christians alike. It makes me throw up my hands in despair!

The biggest argument I can make against “The Original Rubaiyat” would infuriate this sincere, if overzealous duo: Fitzgerald is more fun. I don’t care about poetic credentials — or even accuracy! — Graves’ translation can’t compete! A cook doesn’t get points for accurately following the recipe of an ancient chef: diners only want to know if it tastes good now. Millions and millions of people ordered the Fitzgerald special. Sure he left out a lot of ingredients, and added some of his own, but people are still savoring his dish.

The Curse of the Great Omar

The Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, has one of the largest collections of Rubaiyat-related materials in the world. But there is one book it doesn’t have: The Great Omar, a specially crafted edition whose covers are embedded with 1,050 jewels. This dryly informative video delivers quite a jolt when the fate of this unique book and the man who made it are revealed.

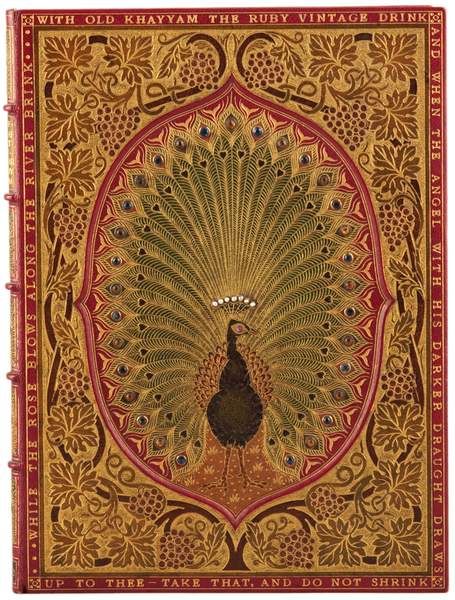

Beautiful Editions of the Rubaiyat

I hate the Kindle — and all eReaders — for a number of reasons, but the primary is one of aesthetics. A digital screen will never match the beauty of a well-made, finely illustrated book.

Here are some images of Rubaiyat covers I have gleaned from Pinterest. In the future I might expand and revise this post to include more details about the various editions. It would bring me great joy to own one of my own.

‘”’

Omar Khayyám — functional alcoholic?

I have only begun to appreciate the poetry and philosophic outlook of the great Omar Khayyám. After reading Edward Fitzgerald’s translation, I wondered: in picking and choosing from Khayyám’s quattrains, did he place undue emphasis on the poet’s celebration of wine? I went on to read Justin McCarthy’s lengthier prose translation, which reveals an even more pronounced prediliction for the Grape. It was this translation that made me think Omar has a problem. His exhortations to the reader can become downright wearisome. Like an argumentative drunk, he gets annoyingly repetitive, and keeps urging us to drink. Fitgerald’s Khayyam wants us to drink and be merry, to delight in the company of friends and lovers, to dwell in the here and now. McCarthy’s Khayyam seems more like an addict trying to drown his sorrow. Here are some examples from McCarthy’s translation that cried out for an intervention, but made me smile:

XXVII.

“I wish to drink so deep, so deep of wine that its fragrance may hang about the soil where I shall sleep, and that revellers, still dizzy from last night’s wassail, shall, on visiting my tomb, from its very perfume fall dead drunk.”

XCVI.

“The world upbraids me as a debauchee, and yet I am not guilty. Ye holy men, look upon yourselves, and learn what ye truly are. You charge me with violation of the Holy Law, but I have committed no other sins than riot, drunkenness, and adultery.”

CCLXXXIII.

“Behold the dawn arises. Let us rejoice in the present moment with a cup of crimson wine in our hand. As for honour and fame, let that fragile crystal be dashed to pieces against the earth.”

Drinking at dawn — always a bad sign.

CCLXXXV.

“See that thou drinkest not thy wine in the company of some clown, riotous, having neither wit nor manners. Nothing but dissensions can come of it. In the night time thou wilt suffer from his drunkenness, his clamour and his folly. On the morrow his prayers and his penitence will cause thy head to ache.”

Choose the right drinking buddy. Wise words from Old Khayyam!

CCCLXXXV.

“I can renounce all, but wine — never. I can console myself for all else, but for wine — never. Is it possible for me to become a good Mussulman, and to give up old wine? — Never.

Rehab is for quitters!

CCCCXXXII.

Do not riot in the tavern; abide there without brawling. Sell your turban, sell your Koran to buy wine, then hurry past the mosque without going in.

And here are a few single lines to make my point:

“My happiness is incomplete when I am sober.” (96)

“Yes, the misery of this wretched world is a poison — wine is its only antidote.” (213)

“A mouthful of wine is better than empire.” (402)

Could it be that the Khayyám of the Rubáiyát is an exaggeration or caricature of the poet himself? I find it hard to believe that he could have functioned as an astronomer — who took meticulous measurements to develop an incredibly accurate solar calendar — and as a drunkard. He was also a leading medieval mathematician. Did he write his treatise on algebra while nursing hangovers? Who knows. At least he knew how to have a good time.

Poetry for the Drinking Man : The Rubaiyat

XXII

Seek the company of men of righteousness and understanding, and fly a thousand leagues from a man without wit. If a wise man giveth thee poison, fear not to drink thereof, but if a fool offereth thee an antidote, pour it out upon the earth.

My study of The Rubaiyat, that is, “The Quatrains” of Omar Khayyam, continues. I’m reading from a collection of three translations combined in one volume. It seems disrespectful to read Khayyam’s work from a cheap paperback, when you consider how many beautifully illustrated editions have appeared in the past. To imbibe his words in such a fashion is akin to drinking fine wine of excellent vintage from a Dixie cup. Furthermore, the Bardic Press edition (2005) I purchased is rather slipshod in its production, with minor errors here and there (such as ”quotation” marks facing the wrong way and misplaced, commas). I wouldn’t recommend it.

I’m currently making my way through the Justin McCarthy translation, which is quite different from Fitzgerald’s.